El Calpense was a newspaper in the Spanish language established in Gibraltar in 1868. It reported on issues regarding the Spanish flu pandemic locally and was more critical of the Sanitary Commission. On the 16th October 1918 they stated that out of 38 deaths recorded in a week, 12 were foreigners who had died in the bay. They questioned the transfer of shipping cases to the Colonial Hospital rather than to the Lazaretto at “La Laguna”. They followed this up with more criticisms and here is an excerpt taken from El Calpense newspaper on 21st October 1918 translated from the Spanish:

“The Lazaretto continues to remain unused as a hospital for cases of Spanish flu and our observations have been well received by everyone except those who could have put this into practice. Even the mule attached to the Sanitary Commissioners’ cart agrees as it refuses to mount Hospital Hill and other means are needed to convey a patient. Anyhow the cases may be diminishing but the deaths are not.

On Saturday evening a patient from the bay was conveyed to hospital in a cab. It was thought that a patient was being conveyed but on arrival a corpse was found. He died in the cab on the way. We are not aware whether the cab was disinfected but it should be. No one can make us believe that the bringing of patients from the bay is not a danger to public health. We appear to be preaching alone, for some time, to deaf ears”.

El Calpense highlighted not only the non-usage of the Lazaretto at the Inundation (“La Laguna”) but also the use of a cab or public hackney carriage for the transfer of infected patients. It is obvious there were issues regarding the landing of sick patients and the transfer to the Colonial Hospital and the need for disinfection of the carriage used to transfer.

There were serious concerns regarding possible transmission of disease to others from such sick patients. El Calpense suggested that the removal of infected cases from the shipping to the Colonial Hospital was the principal cause of the outbreak in Gibraltar.

The Public Health Ordinance of 1907 stated it was an offence for any person suffering from any infectious disease to wilfully expose himself without proper precautions against the spread of the said disease in any street, public place, shop, inn or public conveyance or enters any public conveyance without previously notifying the driver who in turn would be obliged to refer the cab to the MOH for disinfection.

The case referred to by El Calpense came to the attention of the Colonial Secretary who asked for particulars about the case. This patient was a boatswain from the S.S. Maindy Court who apparently died in a public hackney carriage on the way to hospital.

The Secretary of the Colonial Hospital answered that when the man arrived in a hackney carriage, accompanied by a clerk from the shipping agent, at the gate of the hospital he was already dead, and the Surgeon found him dead on examination. The body was taken to the mortuary and he was buried the following day. The Captain of the Port reported that a dockyard launch was sent out to the S.S. Maindy Court which had arrived 19th October to land the sick man suffering from pneumonia.

The Sanitary Commissioners, after consulting the MOH, wrote to the shipping agents asking why they had allowed an infectious case to be exposed, without proper precautions against the spread of the disease, in a public conveyance contrary to the provisions of the Public Health Ordinance 1907 and for not advising the driver to report to the MOH so that the vehicle might be disinfected.

There was at all times a Sanitary Commissioners’ ambulance in readiness at Waterport Wharf for conveyance of patients to hospital and public hackney carriages should not have been used for transfer of shipping cases with probable influenza. Another similar case was reported later from the S.S. War Rose. This issue regarding the transfer of flu patients to hospital in public ‘cabs’ came to the attention of the Sanitary Commissioners towards the end of the second wave and it is possible other cases occurred earlier.

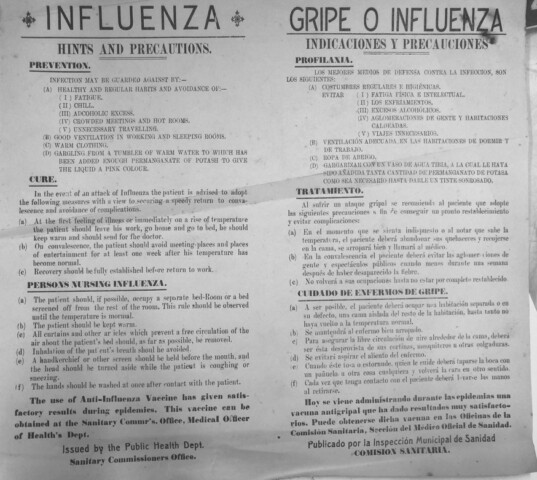

El Calpense explained the steps taken by the Spanish Home Office to prevent the flu. Madrid apparently stated that the ‘germs’ entered via the mouth and nose when breathing so thus disinfection of these cavities was advised. They recommended self-treatment with ‘biclorol’, which was a mixture of sodium chloride, bicarbonate and borate. The mouth was treated by gargling and the nose by wiping the nasal cavity with cotton wool balls soaked in ‘biclorol’.

There were problems with the supply of fresh milk, which was limited. Spain temporarily prohibited its importation into Gibraltar. Arrangements were made to pool the milk available and this was prioritised for the sick, young children and those issued with medical certificates. There were difficulties dealing with the disposal of manure from stables and cowsheds owing to the prohibition of its exportation to Spain. The Sanitary Commissioners overcame this problem by compressing it and burying it at Catalan Bay Quarry covering it with layers of earth soaked in creosote to ‘prevent house flies breeding therein’.

The Theatre Royal had been rebuilt and inaugurated in 1914 and was thus extremely popular. However, on the 21st October 1918 an order was sent from the Colonial Secretary to the Director of the Theatre Royal to close down on one day’s notice, resulting in disruption of existing contracts and difficulties. The Theatre Royal had been in regular operation holding events such as a cinematographic display, variety entertainment, La Bailarina Luna Benamor, Troupe Hermanas Gomez and film exhibitions.

The Gibraltar Public Assembly Rooms and Masonic Hall Ltd. and the Salon Ideal were also closed down on 22nd October. The Assembly Rooms regularly hosted dance clubs such as the Amoureuse, United Service, Victoria Quadrille and Travesties clubs and these events were cancelled. Most clubs, coffee houses, tavern schools and churches remained open it seems and it was argued by the Theatre Royal that the public were being diverted from a well-ventilated theatre to crowded taverns etc.

Andrew Sene is a former Surgeon General at St Bernard’s Hospital and this series was produced with contributions by Anthony Pitaluga, Head of the Gibraltar National Archives.