I don't believe fires are a simple matter that any layman can easily determine things from a few photographs.

Here are some quotes from a member of the incident management team with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, Jonathan Pangburn, from this article

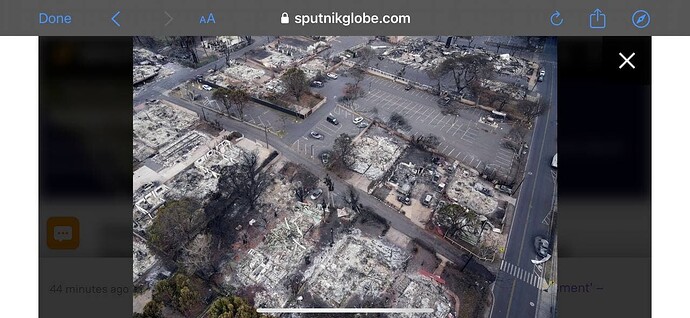

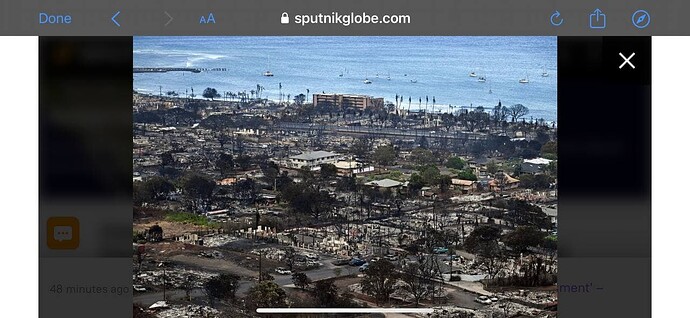

"....Fires that spread from house to house generate a force of their own. Embers, broadcast by the wind, find dry leaves, igniting one structure then another, and the cycle is perpetuated block after block. Break that cycle and the fire quits, and destruction can be minimized."

Most telling were the trees. Most of the pines that sheltered this community still had their canopies intact. The needles, yellowed from the intense heat, were not burned — evidence that the winds that morning had pushed the fire along so fast it never had a chance to rise into the trees. But as a surface fire, it lit up the homes that lay in its path...."

....

"....The phenomenon in Paradise that Pangburn described — the fire spreading from structure to structure, tree canopies intact — is not unique to the Camp fire.

Fire behaviorists have documented it throughout the West, most recently in the aftermath of the firestorms that ravaged Northern California last year.

In spite of this, the popular perception is that wildfires burn through these communities like a wall of flames. In fact, small, burning embers — firebrands — blown in advance of the fire are the primary cause of structural fires.

“When we look at the big flames but not the firebrands, we miss the principal igniter and pay attention to the show,” Cohen said.

Billions of these embers fly into neighborhoods, landing onto flammable roofs, into vegetation around the structure and rain gutters choked with leaves and needles.

Big flame fronts, on the other hand, are less effective in igniting structures because they burn fast — often consuming their fuels in about a minute or less in one location — and move along often so quickly as to not consume the structures themselves....."

Or: Dr. Jennifer Marlon, a professor and researcher at Yale's School of Forestry and Environmental Studies in this article

Another aspect of wildfires contributing to this is that houses are especially vulnerable to embers that spurt off from the flames.

“Embers can be blown for miles ahead of a fire front,” said Susan Kocher, another forest advisor with the University of California Cooperative Extension. “The embers can penetrate the home through the vents or open windows and catch the home on fire, which then burns the trees immediately surrounding the house.”

Kocher said there are cases where neighborhoods catch fire even when the forest immediately surrounding the community isn’t burning because these embers can be blown in from more distant wildfires. Valachovic explained that it can lead to home-to-home ignitions, turning a forest fire into an urban fire.

Maroon said, “Man-made structures have many little holes where embers can fly or get sucked INTO the house and then it's all over (like vents, windows, etc.). And homes have many flat surfaces whereas trees (especially pine trees) are more triangle-shaped to shed particles (like snow) so that they just fall off or through the needles to land on the ground. Anywhere an object can land on a flat surface and sit there is a problem when you're talking about windblown particles.” She said this is especially a problem when those windblown particles can collect together, such as in roof gutters where leaves are piled up or in the V-shaped areas where two parts of the roof meet.

Finally, wildfires don’t always decimate one area cleanly. “The structure of objects themselves, as well as their configuration on the ground, determines how the fire will move and affect things,” Marlon said. “Wildfires naturally burn in a very ‘patchy’ formation because of these differences in fuel shape and structure.”

more discussion