This video breaks down how Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) is working with the World Health Organisation WHO), the World Economic Forum (WEF), Bill Gates and Israeli Intelligence (Mossad) to bring us a whole new concept of health. Not for our well being but as a means of control, described as Orwellian, Brave New World and Animal Farm agenda called "The Long Term Plan" which includes all of world society being run by the NHS.

THE NEW NHS WORLD ORDER - SCANDAL

England to be the worlds first smoke free society, housing provided by the NHS with 24/7 external and internal surveillance. New "healthy towns" being built now and healthy awards for your home and business as long as you comply. Linked to your genome, health passport and NHS App. This is the social credit system in action.

So join me on the edge of the simulation, as we delve into the real agenda. Frightening doesn’t go far enough for this new society being created and it’s here already!

Here the links to The Long Term Plan https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk

https://www.thetruthseeker.co.uk/

This also ties in neatly with their concept of total control

Technology Quarterly | One ring to rule them all

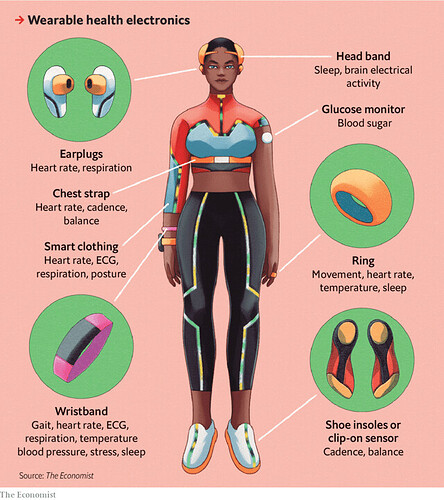

Wearable devices measure a growing array of health indicators

They can detect a disease before it develops

On the outside, the Oura ring looks rather ordinary, indistinguishable from a chunky wedding band. But a faint green light that intermittently leaks out from the gap between finger and ring suggests that it is not just jewellery.

The inside of the ring is packed with electronics. The green light comes from a pair of rectangular metallic specks that are light-emitting diodes, or leds. Three dome-shaped bumps the size of water drops contain red and infrared leds and a pair of photodetectors. They are surrounded by seven temperature sensors, a wafer-thin battery and a miniature 3d accelerometer that detects any kind of motion.

What a wearable device can measure depends on its sensors and its software. Lower level algorithms turn the noisy output of photodetectors and the like into heartbeats. Higher level programs combine, say, heart rate, temperature and movement into measures of the duration, and quality, of sleep.

Sensors and algorithms combine to help wearable devices measure step counts, calories burned, oxygen levels and more. Artificial intelligence (ai—as machine learning is popularly known) gives extra oomph to the algorithms. Technology advancements in the past five years have made it possible to pack wearable devices with more sophisticated sensors and more computing power. Oura’s third-generation ring, released three years after the second, has 32 times more memory with the same battery life.

All that has enabled wearables to produce more accurate measures and a greater number of them. In a recent review

iqvia, a research firm, found 384 wearable devices marketed to consumers. They include wrist-worn fitness trackers, sports watches, smartwatches, smart jewellery like the Oura ring and sensor-bearing headsets, patches, straps, clip-ons and even clothes (such as smart socks that measure the vitals of babies). Just over half of the devices analysed by iqvia monitor activity. The rest are devices that measure a wide array of health variables, including sleep, temperature, breathing, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, blood sugar and electrical activity of the heart.

Tracking digital biomarkers allows wearables and their associated software to identify changes that are early signs of disease or age-related deterioration that may otherwise go unnoticed. Take atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heartbeat that increases the risk of stroke. About 9% of Americans over 65 and 2% under 65 have the condition, often with no symptoms to alert them to it. In 2018 the fda approved the Apple Watch as a device that can identify atrial fibrillation. It issues an alert when it spots a string of irregular heartbeats. The user can put a finger against a sensor on the side of the watch, which sets up a circuit sensitive to the heart’s electrical activity, allowing the watch to produce an electrocardiogram (ecg). On April 11th Fitbit got fda approval for its own atrial-fibrillation function.

Movement, an irksome source of noise for individual sensors, is a valuable ingredient in many digital biomarkers. Gait changes, for example, can show whether a person’s balance is deteriorating. A recent study found that people who have early-stage Parkinson’s disease have subtle differences in gait, arm swing and how they type compared with those who do not. All were measured by their phones and wrist-worn devices. The digital measures also reliably tracked how far the disease had advanced.

Currently, depression is diagnosed using a standard set of questions. Algorithmic measures of the sentiment in daily voice diaries can do the job just as well. Some virtual providers of therapy and psychiatric care are already using interaction patterns between people and their smartphones (without capturing the actual content of what is typed or viewed) to track the mood and cognitive state of patients.

Wearables can also spot healthy changes that people want to know about. Upticks in temperature, for example, are markers for ovulation and pregnancy. Oura is testing a feature predicting weeks in advance the date of a woman’s next period. A small study found that measurements from the ring could detect pregnancy on average nine days before at-home pregnancy tests.

There is almost no part of human biology that has remained untouched by digital measurement. HumanFirst, an organisation in San Francisco that maintains a catalogue of connected devices for remote patient monitoring, has identified 1,200 digital sensors that are tied to 8,000 physiological and behavioural measures.

Andy Coravos, the chief executive of HumanFirst, has a worry about unregulated devices. Some collect information that is not currently protected as health data, she says—which means it could be used to target advertisements or possibly discriminate when it comes to health insurance or employment. A neurological symptom such as a tremor, for example, could be collected as “wellness” data and reveal a high likelihood for a disorder such as Parkinson’s disease, says Ms Coravos. Insurers can get hold of this information via online data brokers and charge that person a higher premium.

Wearable devices measure a growing array of health indicators https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2022/05/01/wearable-devices-measure-a-growing-array-of-health-indicators