The fishing activity (associated with the salted fish industry, the production of amphoras, and the export of salted fish, especially tuna) represented the most powerful and profitable of all the activities developed in the city and its surroundings, since the salted fish factories and pottery industries run by citizens of Carteia, rich and powerful families such as the Numerii, Vibii, and Minii, were located throughout the coastline from Villa Victoria (Puente Mayorga) to the Palmones River area: the Venta del Carmen pottery (Los Barrios).

Ancient sources are abundant in mentions of the fishing wealth and associated industries established in Carteia and other cities of the so-called "Strait Circle" in Roman times. Geographers, naturalists, and numismatic evidence abound with data relating to the variety and abundance of the products of the land, the generosity of the bay waters in species of fish and shellfish, and the industrial power around shipbuilding, fish salting, purple production, or pottery in the area. All of these economic activities were linked to an active maritime trade confirmed by the shipwrecks found in the bay waters, the remains of salted fish amphoras scattered throughout the Mediterranean and even in the Germanic and British "limes" from the local pottery workshops, as well as the coin findings of the local mint made in distant places that indicate the vigorous commercial activity that Carteia reached.

Numerous material testimonies have been recovered that demonstrate the economic importance that fishing and its industrial processing acquired in the Phoenician settlements of the western Mediterranean, with the Phoenician factory of Cerro del Prado being no exception. This factory was located next to the Guadarranque River and was active between the 7th and 4th centuries BCE. Fish, mainly tunas, caught using a technique known in the Andalusian period as almadraba or jábega, was processed on an industrial level in specialized coastal factories using salting methods to achieve its preservation and to allow it to be commercialized and exported by sea in ceramic containers that traveled to other places in the Mediterranean, the East, Britain or Germania.

Many classical writers describe the abundance of fish that were caught and the enormous wealth that fishing generated for the populations located on both sides of the Strait, both in the Phoenician-Punic period and in the later Roman period, as explained in the well-documented article "Archaeology of Fishing in the Strait of Gibraltar. From Prehistory to the End of the Ancient World" by Professor Darío Bernal Casasola. It is true that from the end of the Roman Republic, after the last Civil War - perhaps due to the support of the Carteians to the cause of Pompey, the loser in that war - there are very few written sources about Carteia. However, thanks to the production of coins and the texts of the geographer Strabo (1st century BC and 1st century AD) and the naturalist Pliny (1st century AD), we have revealing data regarding the fishing activity of the city.

Strabo states (Chapter III, 2, 7): It is said that in Carteia, buccinum and murex shells have been found that can contain up to ten kotilay (about three kilograms); and off the coast, moray eels and conger eels weighing more than eighty mnai (about thirty kilograms) are caught, as well as octopuses weighing a tálanton (about twenty-six kilograms), squids two cubits long, and so on. Many tuna fish that come from the Outer Sea to these coasts are fat and greasy. They feed on the acorns of a certain low-lying oak tree that grows near the sea, which produces truly abundant fruits...; however, they produce so many that after high tide, both the coast of the inner part and the outer part of the Pillars are covered with those that the tide brings in... And the closer the tuna fish come from the Outer Sea to the Pillars, the thinner they become, due to lack of food.

Pliny writes in his Naturalis Historia (Book IX, 92-93): Trebius Niger, from the entourage of the proconsul of Baetica, L. Lucullus, tells that there was an octopus in the ponds of Carteia that used to come out of the sea and approach the open ponds, ravaging the salted fish... which aroused the excessive indignation of the guards due to its continuous thefts. Fences protected the place, but it climbed over them by climbing a tree; it could not be discovered except by the sagacity of the dogs, which saw it one night when it was returning to the sea. The guards were amazed at the spectacle, first because of the size of the octopus, which was enormous; then because it was completely covered in brine, emitting an unbearable odor... It frightened the dogs away with its terrible breath, sometimes whipping them with the ends of its tentacles or striking them with its very strong arms, used like clubs. It was only with great effort that it could be killed with tridents. Its head, which was the size of a dolium capable of containing fifteen amphoras, was shown to Lucullus; repeating the words of Trebius himself, I will say that its beards could hardly be encompassed with both arms and were knotty like clubs, with a length of thirty feet. Its suction cups were like pitchers, resembling a basin; the teeth were of the same proportion. The rest of the body, which was kept for curiosity, weighed seven hundred pounds. The same author asserts that on these beaches, the sea also throws cuttlefish and squids of the same magnitude.

Both texts reveal the importance of fishing and the industrial process of preserving fish products in cities located on the shores of the Strait. Strabo likely obtained the data from Posidonius, who was on the coasts of Gades at the beginning of the 1st century BC. The Greek geographer extensively describes the abundance and quality of the fish that inhabited the waters of the Fretum Gaditanum, alluding to a species that has been the basis of fishing and the fishing industry on both sides of the Strait since prehistoric times: the bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus).

Although Pliny's account, which describes a giant-sized octopus, is fantastic, it is still of special interest for the knowledge of the exploitation of marine resources in the city of Carteia, as it mentions "cetarias" (pools) where pieces of tuna were placed in brine for maceration, which have been documented by archaeology in Carteia, Iulia Traducta, Baelo Claudia, Mellaria, etc.

In addition to the architectural remains and other movable materials, numerous bronze hooks have been recovered in the excavations carried out in the city of Carteia. In a work carried out at the Acerinox factory (Los Barrios), a fish plate was found and is currently preserved in the Municipal Museum of Algeciras.

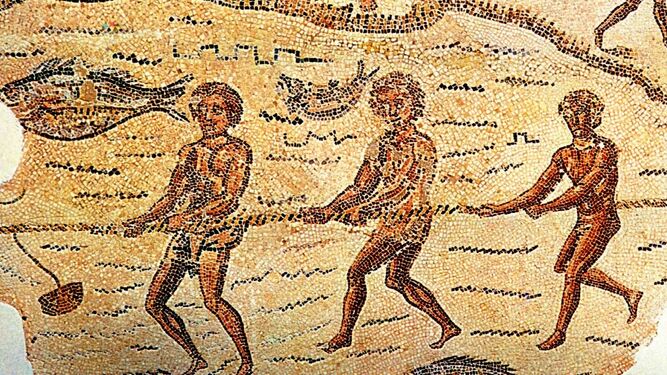

Regarding the arts and methods of fishing, in Carteia, as in the rest of the cities of the Mare Nostrum, a wide variety of methods and different arts were used to catch fish, cephalopods, crustaceans, and mollusks. Although there are no mosaics with representations of fishing scenes in the coastal cities of Bética, numerous mosaic testimonies from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD are exhibited in the Bardo Museum in Tunisia, which allow us to know the various fishing techniques used in Roman times. Individual fishing with a cane, harpooning cephalopods with tridents, the use of traps, seine fishing, cast nets, and the jábega are documented. The gathering of limpets, snails, and periwinkles is documented by the presence of the shells of these mollusks in the excavated sites in Algeciras (Iulia Traducta, on San Nicolás Street) and Baelo Claudia. Recently, a purple production workshop has been located in the extramural area of Carteia (Villa Victoria, Puente Mayorga), with a large shell mound where remains of nineteen species of malacofauna have accumulated, dated to the 4th century AD.

A preserved salting factory was excavated on the site of Villa Victoria (San Roque) (E. García Vargas and D. Bernal Casasola).

The importance of fishing and the industrial process of preserving fish products in the cities settled on the shores of the Strait is revealed in both texts. Strabo likely obtained the data from Posidonian, who was on the coasts of Gades in the early 1st century BC. The Greek geographer elaborates on the abundance and quality of the fish that populated the waters of the Fretum Gaditanum, making reference to a species that, from prehistoric times to the present day, has been the basis of fishing and the fishing industry on both sides of the Strait: bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus). Although Pliny's account, which describes a giant-sized octopus, is not without its fantastic elements, it is still of special interest for understanding the exploitation of marine resources in the city of Carteia, as it mentions the "cetarias" (fish tanks), in which pieces of tuna were placed in brine for maceration, and which have been documented by archaeology in Carteia, Iulia Traducta, Baelo Claudia, Mellaria, etc...

Excavations carried out in the city of Carteia have yielded, in addition to architectural remains and other movable materials, numerous bronze hooks. In a project carried out at the Acerinox factory (Los Barrios), a fish plate was found and is now kept at the Municipal Museum of Algeciras.

Regarding fishing techniques and methods, a wide variety of methods and different techniques were used in Carteia, as in the rest of the cities of the Mare Nostrum, to catch fish, cephalopods, crustaceans, and mollusks. Although coastal cities in Bética do not have mosaics with representations of fishing scenes, the Bardo Museum in Tunis displays numerous mosaic testimonies from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD that allow us to learn about the various fishing techniques used in Roman times. Thus, individual fishing with a cane, harpooning of cephalopods with tridents, the use of traps, fishing with nets, throw nets, and the jábega are documented. The harvesting of limpets, snails, and winkles is documented by the presence of shells from these mollusks in excavated sites in Algeciras (Iulia Traducta, in San Nicolás street) and Baelo Claudia. Recently, a purple production workshop has been located outside the walls of Carteia (Villa Victoria, Puente Mayorga), with a large shell deposit that accumulates remains of nineteen species of malacofauna, dating back to the 4th century AD.

One cannot fail to mention the coin emissions of Carteia, which depict images related to the marine world and fishing to demonstrate the importance that the exploitation of sea resources had for the city. On the reverse of some coins, a fisherman with a cane and a basket for depositing catches, dolphins, ship's prows, a rudder, etc., are depicted. Dolphins, which symbolize navigation and were protective for ships, also appear engraved on Roman lead anchor stocks recovered from the waters of the Strait. The figures represented on the coins had, in addition to their nominal value, the function of capturing prominent aspects of political, social, or religious life, as well as exposing and advertising the images that represented the most prominent economic activities of the city, whose diffusion was directly related to the commercial boom of Carteia society, and therefore can serve as an element of analysis to understand the development of Carteia, its economic potential, and the geographical projection of its economy.